Letter From the Desert: Dragon Bravo and the Grand Canyon Lodge

On losing things you never knew.

On June 2 of this year I made a seemingly trivial decision I now regret deeply.

I was at a gas station in Shonto, on the Navajo Reservation. I wasn’t feeling completely well, and I was a trifle homesick. I had a choice to make. The most direct route home was south on US 160, which led to Moenkopi, and then — after a few turns onto successively more crowded highways — to Flagstaff and then Williams, two and a half hours away, which stopping point would leave me only four and a half more hours of driving the next day.

Alternatively, a right turn onto Arizona 98 also eventually led home, but at the cost of doubling my time on the road. Route 98 would have taken me to Page and a left onto US 89, then onto 89a, over the Marble Canyon Bridge, and eventually to the North Rim of the Grand Canyon.

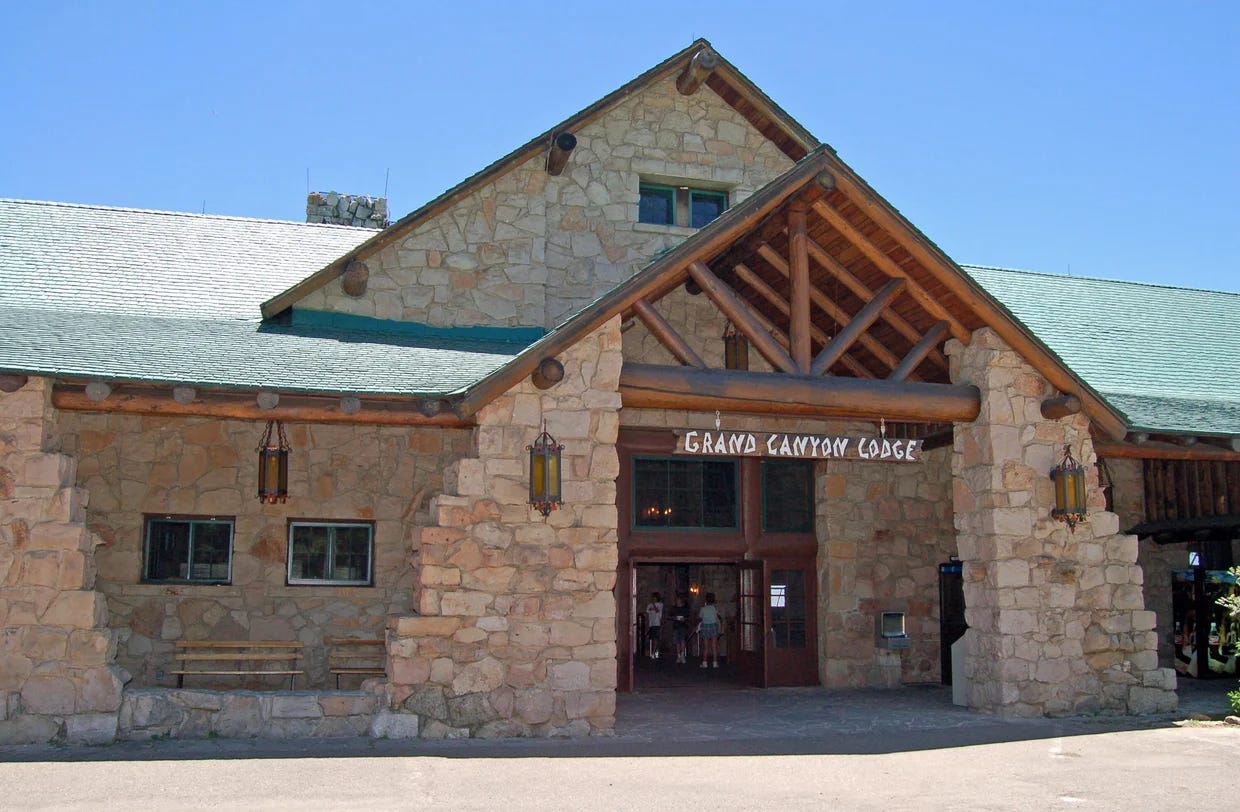

I stood there at the gas pump debating with myself. I’d been away from home for a little over a week, and was feeling a little disheartened and road-weary. On the other hand, the North Rim, home of the Kaibab squirrel, which I’d read about and wanted to see since I was maybe seven years old. After several days in the red rock the forested Kaibab Plateau held a certain appeal, especially since the time of day and lack of the $250 I’d need to stay at the Grand Canyon Lodge even if they had a miraculous vacancy meant I’d be sleeping under some Kaibab Plateau conifers that night.

By now you will have guessed, based on the first sentence in this Letter From the Desert, that I talked myself out of delaying my return home, talked myself out of sleeping with the Sciurus aberti kaibabensis at 7,000 feet, told myself that I had plenty of time to go stay at the Grand Canyon Lodge, preferably with La mujer que amo. It turned out to be a sensible decision. I passed a comfortable but fitful night in Williams, got home early the following afternoon, and slept for two days.

As we now know, I did not have plenty of time to go stay at the Grand Canyon Lodge.

On Saturday, July 12, the Dragon Bravo Fire, which had been burning since a lightning strike in the Kaibab on July 4, grew dramatically as winds picked up. That evening, the fire took out the nearly century-old Grand Canyon Lodge, along with several visitor cabins, employee housing, and some ancillary buildings.

The National Park Service has taken some heat1 for its handling of the fire prior to Saturday. for the week prior to the loss of the Lodge, the Park Service had been responding to the fire with what they call a “confine and contain strategy,” basically allowing the fire to burn, fulfilling its needed ecological role in a forest that evolved with occasional fires, while trying like hell to keep it from spreading. That clearly didn’t work. Arizona electeds are demanding an investigation of whether NPS responded adequately to the fire before July 12.

Determining whether the Park Service erred basically means finding answers to the following questions:

Was Confine and Contain the appropriate strategy given the dehydrated state of the forest?

Would it have been possible to come anywhere near extinguishing the fire if the Park Service had decided on a suppression strategy?

Given the 40 mph winds that hit Saturday, would a few days of fire suppression even have made a difference?

I have no idea what the answers are to any of those questions. I am mindful of the fact that firefighters had declared a small grass fire in the Berkeley Hills under control on a Saturday in 1991, and the following day that fire escaped control and proceeded to burn down 3,280 homes2 and kill 25 people.3 If firefighters had been able to knock the Dragon Bravo Fire back to a few hundred smouldering acres before the 12th, it’s not unlikely that high winds would have kicked the fire back into high gear.

Unlike the aforementioned Oakland Hills Firestorm, Dragon Bravo does not, at this point, have a (human) body count. That is a remarkable blessing. Not only did everyone evacuate the North Rim successfully as Dragon Bravo surged from roughly 3,000 acres to around 4,300 by the end of Saturday, but the Park Service also safely airlifted visitors and staff from Phantom Ranch on the Colorado River when the North Rim’s destroyed water treatment plant sent a cloud of chlorine gas rolling down Bright Angel Creek.

All that said, there are questions to be answered, including whether recent gouges in the National Park Service’s budget and staff complement hampered efforts to hold Dragon Bravo back. (The Bloated Billionaire Bailout Bill contains measures to consolidate all federal firefighting crews into one agency, which may be bad news for those contending with future fires, but that wasn’t an issue with Dragon Bravo, I don’t think.)

Here’s one thing I do know: Right now, within about a hundred fifty miles of the North Rim, there are 117,271 acres burning, the largest single fire among them being the 53,000-acre White Sage Fire about 50 miles north of the North Rim.

A combination of a century of misguided fire suppression and an equivalent span of our monkeywrenching the climate has brought us here.

In this context, losing a building mainly used for enjoyment might seem rather trivial, and I suppose it is. But I’ve been thinking about the Grand Canyon Lodge’s counterpart on the South Rim, the El Tovar, where I stayed for a night in 2005 before hiking down to the river. The afternoon before the hike, I was relaxing on a balcony of the building with my friends Bill and Joan, sitting in a chaise longue drinking a root beer or something similar, when I saw a California condor — my first — gliding about 20 feet overhead.

It strikes me that my feelings about losing the Grand Canyon Lodge are remarkably similar to my feelings when I heard the last wild California condor had been captured for the feds’ captive breeding program: grief over the loss of something I never knew. The Fish and Wildlife Service has worked to rebuild the condor population — thus my sighting from that chaise longue in 2005 — and it may be that the Grand Canyon Lodge will be similarly rebuilt. But I wouldn’t bet on that happening anytime soon.

Unless, of course, it’s rebuilt as a 30-story gold-plated tower with a reviled five-letter surname on the top and substandard, tacky fixtures inside. I bet Congress would pony up the cash for that.

I honestly don’t know whether this pun is intended.

2,843 single family homes and 437 apartments/condos

The firestorm also killed my friend Su’s sweet cat Oliver and an estimated 800 other cats and dogs.